|

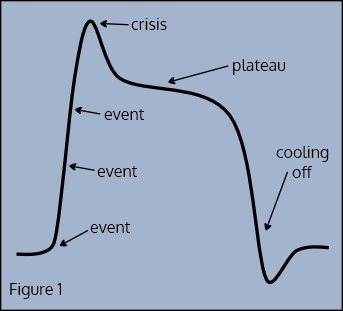

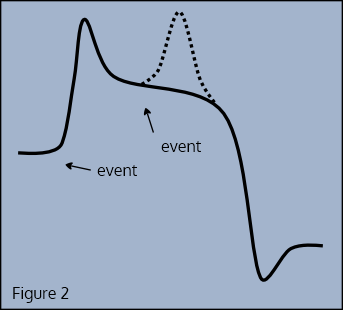

Anger management is an often used term. One of the misunderstandings about anger management is that it is about the teaching of various techniques to control it, such as using breathing, mindfulness, or ways to openly express it. And while these techniques can be useful in helping to manage anger, they are a bit like putting a plaster on a cut - they help to make anger less painful and distressing. The two key elements to managing anger are 1) becoming more aware of when you are angry, and 2) understanding how you respond to anger. In this three part article I will be looking at understanding anger based on Breakwell's 5 stage model (1), and how you might use these insights to gain more control over anger.  This model represents how we typically react; however each of us is an individual so your reaction may not quite look like this. The black line represents the level of anger, and Figure 1 is how someone will react during a prolonged event such as an argument. The person starts initially at a low level, and responds to an, ● event. Anger is always a response to something, and it is not the event itself, it is the meaning we make of the event that gets us angry. People can get angry at internal events such as thoughts or memories as well as external ones such as being shouted at. With each event the level of anger rises until, ● crisis. The person loses control. How someone behaves in crisis is very individual to them, and will usually last from a few seconds to a minute or two. They then, ● plateau. In this stage we are still very angry, and can easily enter crisis again. Outwardly the person can appear to be calm. Inwardly, we can feel as though we are holding on to our anger, or some people can feel quite calm. The length this stage lasts depends on how angry the person got, and it typically lasts much longer than you might imagine. It can take anything up to 90 minutes before we begin, ● cooling off. We usually experience this as a dip where we can feel tired, and/or tearful, and may be accompanied by feelings of remorse and guilt. Sometimes a single event can set us off This is often because of something known as a setting event. This is something going on in the background that pushes our level of arousal much higher than normal. This can be caused by things like stress at work, or feeling unwell. Figure 2 shows what this looks like with a second crisis as a dotted line. It can look something like this,  Steve* is on his way to work, his company has been in financial trouble, and there has been talk of redundancies. When he arrives, there is an air of tension. He joins in the conversations which shift back and forth from "The problem is the management should be doing more," to "Well whatever is going to happen will happen," to the dark humour that often accompanies such situations. On the way home, there are road works and he spends the time in a frustrating queue. When he finally gets home, his partner is annoyed, because he forgot he was supposed to have picked up something for dinner, at which point a row breaks out. As he is driving to the supermarket with his partner in an awkward silence, he decides to open a conversation by explaining again why he forgot, and his partner replies "I've had a hard day too!" At which point another row breaks out. In the example above the setting events are the work situation and the drive home. By the time Steve gets home, his level of arousal is high enough that his partner being annoyed with him provokes a crisis - the row. The meaning that he makes of the event might be something like "My partner doesn't appreciate what a bad day I've had." The second row is triggered because both of them are still in the plateau phase, and are both still highly aroused. His attempt at trying to make himself understood only serves to reinforce his feeling his partner does not appreciate how hard his day was. Notice that it is the meaning Steve makes of the event rather than the event itself that makes him angry. The example draws out two important points,

In Part Two, I will be looking in more detail at how you can use this model to work with feelings of anger. References (1) Breakwell G M (1997) Coping with Aggressive Behaviour Leicester: British Psychological Service. A shortened downloadable PDF of this article is available here *Steve's story is a fictitious event based upon my experience of talking to people about their anger.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2021

|

BioI'm Mark, a Humanistic Counsellor. |

Home - Testimonials - Articles - Links - Contact - Book Appointment - Counselling Students - Privacy Policy - Terms

Mark Redwood, BA (Hons) Counselling, MBACP

© Mark Redwood 2015, 2016.2017 | Main portrait by Doug Freegard © 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed