|

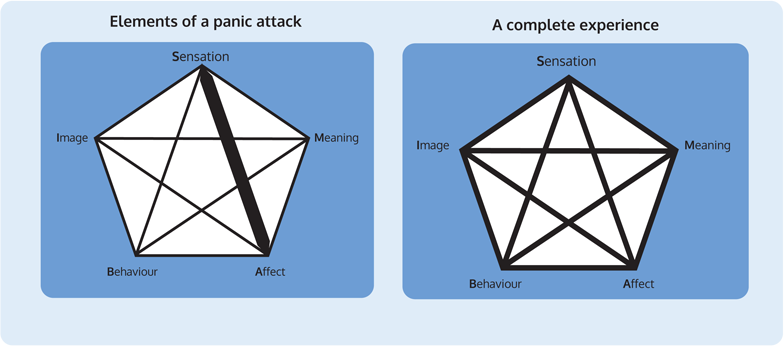

In my previous article Mindfulness & Safety, I looked at practical ways to stay safe while doing mindfulness. In this article I am going to take an in-depth look at the relationship between mindfulness and dissociation, which is associated with traumatic experiences. What is dissociation? Dissociation is where we split off some parts of our experience. When dissociation is a response to trauma, it is believed to be a protective mechanism, which prevents the person becoming overwhelmed. Dissociation can also be a pleasant experience, such as when we daydream, or take psychoactive drugs. When I started to read the stories, by Dawn Foster and Willoughby Britton, I realised I was very familiar with them. What they were describing were traumatic dissociative experiences being triggered by the practice of mindfulness. A useful way of understanding what was happening is by using Peter Levine's, SIBAM model. He proposed that our experience is composed of 5 elements,

During a 'complete' experience, all 5 elements are available to us, I am sitting in restaurant, seeing a plate of pasta, and I remember the last time I came (image). I am lifting my fork into my mouth (behaviour), and as I swallow I notice the warming sensation of the food going down (sensation). I have this contented feeling (affect), and I think to myself 'I enjoy coming here' (meaning). During dissociation 1 or more elements become separated off from our experience, and the remaining elements become more intensely experienced. Dissociation is an everyday experience, and if you have driven anywhere today you have probably spent some of that time dissociating. Often when we drive, we aren't concentrating on the road, we're thinking about something else. Perhaps, our thoughts going round and round, worrying about how to deal with the 'knotty' problem that's on our minds. As we do so, we notice less and less we are sitting in a car, driving on a road, so that by the time we arrive at our destination, we find we can't remember the journey. Dawn Foster in her article provides a first hand account of a harmful dissociative experience during mindfulness, and we can use Peter Levine's SIBAM model to understand what happened. Here is that experience in her own words, Then comes the meditation. We’re told to close our eyes and think about our bodies in relation to the chair, the floor, the room: how each limb touches the arms, the back, the legs of the seat, while breathing slowly. But there’s one small catch: I can’t breathe. No matter how fast, slow, deep or shallow my breaths are, it feels as though my lungs are sealed. My instincts tell me to run, but I can’t move my arms or legs. I feel a rising panic and worry that I might pass out, my mind racing. Then we’re told to open our eyes and the feeling dissipates. I look around. No one else appears to have felt they were facing imminent death. What just happened? source Dawn Foster in the Guardian Dawn's description includes all 5 elements of Peter Levine's SIBAM model of experience, some of which are more strongly associated and some of which are dissociated, Heightened Association

Dissociated

What Dawn describes is a panic attack, which is conceptualised in the diagram below. Why might mindfulness cause a panic attack? The western practice of mindfulness focuses on a particular strand of inquiry in Buddhist meditation known as the 'no-self' The practice is one of deliberate dissociation. You sit still to focus on sensations in the body, which slows down the flow of conscious images, which ultimately will allow you to explore a state where you lose your sense of self. Identity is in reality a group of meanings we have about ourselves, and through meditative practice, we can separate from this meaning to explore the 'no-self'. Mindfulness is often understood as a way of relaxing, and coping with stress, which is how it is promoted. Perhaps, a better way of understanding mindfulness is to look at it as being an adoption of a pattern of bodily and mental shapes into which other experiences can fit. One of these is relaxation, but traumatic experiences may also fit into this pattern and may subsequently emerge. Mindfulness opens a door, and it's important to understand that more than one kind of experience can fit through that doorway. For most of us, most of the time, this will be a sense of peace and perhaps wonder. However, other dissociative patterns, such as panic attacks, and previous traumatic experiences, can also fit through the doorway we have created when we practice mindfulness. In the article Dawn describes how she was anticipating an "awkward experience" and noticing how people were nervous in the earlier exercises. Dawn starts the exercise feeling anxious. As she shuts her eyes, and shuts off one element of her experience, she starts focusing on her breathing. Instead of being calming, the exercise amplifies her feeling of anxiety - a panic attack suddenly and unexpectedly fits into the space she has created. The aftermath In the exercise, Dawn is told to open her eyes. As she does so, and looks around the room, her feeling of panic dissipates. By adding back in some of the missing elements - behaviour and image, her dissociation subsides. She also starts trying to add in the final element, meaning, by trying to understand what happened. Dawn's article on one level can be understood to be an investigation into the harmful effects of mindfulness, and it can also be seen as a way for Dawn to make sense of what happened. Dawn also describes the longer-lasting effects of her experience, For days afterwards, I feel on edge. I have a permanent tension headache and I jump at the slightest unexpected noise. The fact that something seemingly benign, positive and hugely popular had such a profound effect has taken me by surprise. source Dawn Foster in the Guardian A dissociative episode is often followed by a period of feeling strange. They typically last from a few minutes to several hours, and they can, as in Dawn's case, last much longer than this. People can also have feelings of disorientation, confusion, being in a fog, unreality, feeling the body is distorted, or a sense of floating. These kinds of sensations can also follow a pleasant dissociative experience. Dawn also describes another common feature of traumatic dissociative experiences, re-triggering. Just thinking about the sensations and feelings, causes the dissociative state to re-emerge. Experiences like Dawn's, led to a realisation that therapy could actually be harmful for people who have been traumatised. Being encouraged to talk in detail about a traumatic experience risks triggering further dissociative episodes, which rather than being healing, is instead re-traumatising. Ultimately, this has led to a shift in how we help people who have had traumatic experiences. Mindfulness in the counselling room Mindfulness is the practice of present moment awareness. This can help in several ways. Often feelings of anxiety are a future moment awareness - we project ourselves into an imagined future. Opening ourselves up to a present moment awareness can help to reduce feelings of anxiety, and give us a sense of control. Feeling more in control can also help us tolerate greater levels of anxiety, increasing our resilience. Many emotions are first perceived as sensations in the body. Increasing our present moment awareness can help us to recognise rising emotions such as anger. Having a greater awareness of present moment sensation and the feelings associated with it can help us to respond more meaningfully to them. As a practitioner, I am aware that there isn't a one-size-fits-all approach. For some people some of these practices, particularly the ones which focus on body sensations such as breathing, can be unsettling and unhelpful. Part of my role is to act as a guide tailoring these techniques to the individual, while retaining awareness of the possible pitfalls. References SIBAM model description, from Babette Rothschild (2000), The Body Remembers pp. 67-70, SIBAM diagram derived from plate p. 69. Title image by miamiamia

3 Comments

20/2/2018 01:56:10 pm

Thank you for this excellent article. I have known this from first person experience for 26 years and now specialize in trauma treatment and feel that all meditation teachers need to understand the concepts that you've put forth so well. I have posted to FaceBook at devpreet.kaur.3 and have used to help trauma survivors understand why mindfulness is not the ideal first meditation technique. Only after mantra meditation (ideally with mudras) calm the nervous system and teach the body-mind to 'stay' should we attempt serious mindfulness training. Thank you again for this post that I have used as a training tool. Wishing you many more years of satisfaction in service.

Reply

Kay

26/6/2021 03:25:47 am

Thank you...This was immensely helpful. I find it fascinating that I found the mention of Headspace in this article. I just started using this app not two weeks ago, several nights in a row...And I have found that I've been increasingly agitated. "Reconnecting" to my body is actually causing me far more anxiety than ever, which I thought was odd...Your doorway analogy is spot-on. I am going to bring this up in my next therapy session to discuss further. I also have trauma in my past and my therapist specializes in it. Thank you.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2021

|

BioI'm Mark, a Humanistic Counsellor. |

Home - Testimonials - Articles - Links - Contact - Book Appointment - Counselling Students - Privacy Policy - Terms

Mark Redwood, BA (Hons) Counselling, MBACP

© Mark Redwood 2015, 2016.2017 | Main portrait by Doug Freegard © 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed